Why does Dialogic Teaching work?

“Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with shades of deeper meaning.” Maya Angelou

In July 2017 the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) published a report showing that Dialogic Teaching supported children in Year 5 (9-10 year-olds) to make accelerated progress in English, science and maths. This is consistent with the findings of a 2016 report showing that regular practice of Philosophy for Children (P4C) has a similar positive impact on attainment in reading and maths for children of a similar age. These findings have led people to wonder about the mechanism through which these approaches (both of which focus on the development of cognitively challenging talk and dialogue) impact on the learning of academic subjects, and in this post I offer some thoughts on this.

One mechanism might involve the role of dialogue / dialogic thinking in the development of conceptual understanding. A sound understanding of key concepts supports the development of knowledge within (and sometimes across) subjects (see Tim Oates’ 2010 report ‘Could do Better‘ and Lynn Erickson and Lois Lanning’s 2014 book on a concept-based curriculum). But coming to understand ideas such as significance, energy, force or love involves more than being given a definition. In our 2017 book ‘Dialogic Education: Mastering core concepts through thinking together’, Professor Rupert Wegerif writes ‘Conceptual mastery is not just about getting new information from a book or the whiteboard; it is about seeing the world in a new way.’

Concepts such as force and love are much less precisely specified in everyday life than they are in the disciplines of science and theology; coming to see such ideas from the perspective of an academic discipline or school subject requires a ‘creative leap‘ and this kind of perspective taking is precisely what is learned when learning to dialogue. Wegerif writes ‘When you engage in dialogue with someone very different from you it is common not to understand them at first. They may seem to have a different way of seeing the world. But by making an effort it is often possible to find points in common, to begin to make sense of where they are coming from and so, finally, to really understand what they are trying to say.’ Getting to know a new concept – and coming to see it from the perspective of a subject – requires the same effort. The student needs to come into dialogue with the subject (which may be embodied by the teacher). Teaching for conceptual understanding means teaching for dialogue.

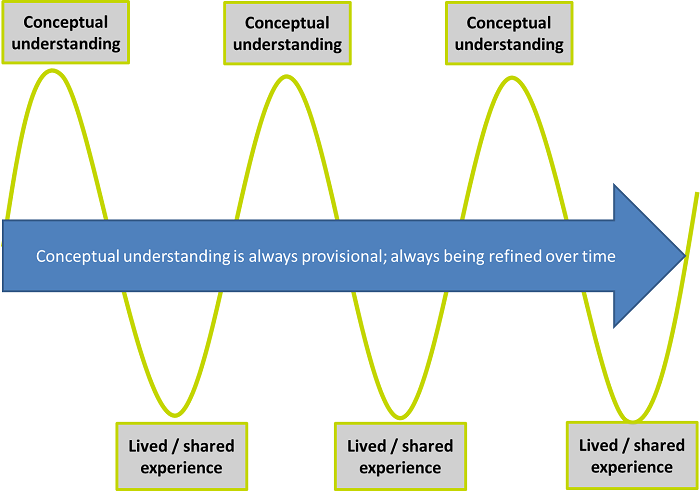

Dialogue also has a role to play in connecting abstract ideas to students’ lived experience which supports the construction of meaning. Moving a dialogue / dialectic between an abstract idea and the shared and lived experiences of the participants helps them to refine their understandings of the idea itself and to make meaning through a connection to the concrete. Erickson and Lanning refer to this as ‘synergistic thinking’; I have given an example of its use in my practice here.

I also believe, and I acknowledge that this is controversial in some quarters, that learning to dialogue develops dialogic thinking skills which are applicable across subjects. As we dialogue we think out loud – we think together. Vygotsky suggested that social interaction is the origin of all ‘higher order thinking’:

“Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first on the social level and later on the individual level; first between people and then inside the child… All the higher order functions originate as actual relations between people.”

Of course it is true to say that thinking is reliant on subject knowledge, but I would argue that to make use of subject knowledge (to problem solve, for example) we need to be able to think well. Dialogic habits such as switching perspectives, searching for examples, offering speculative ways forward etc. are useless without knowledge, but are never-the-less indispensable. These habits are transferable and are learned through learning to dialogue (see this post for a more detailed discussion).

Learning to dialogue and to think dialogically is synergistic with the development of subject knowledge. In this post, Martin Robinson, author of the excellent Trivium 21c, raises concerns that dialogic teaching might encourage teachers and children to ‘move on to arguing about stuff too quickly’. Such argument represents the ‘dialectic‘ phase of the Trivium and may only be useful once subject knowledge – the underlying grammar – is secure. I do understand the concern here, and I absolutely agree that there is a place for ‘closed questions, recitation and brief pupil contributions’ – and listening to the teacher; whilst dialogue is an important part of the repertoire of classroom talk, it is by no means the only medium to be used. However, I would argue that the kind of dialogic teaching reported on by the EEF, and the kind promoted in our book, does not of necessity seek to challenge the grammar and indeed supports its development through the development of understanding of the concepts on which it is built.

That said, I do think that dialogic teaching prepares the way for Robinson’s dialectic in that it teaches that conceptual understanding (and the knowledge that is based on it) is always provisional. A quote I often use (and I think I took it from Martin Robinson) is ‘This is the best that’s been thought and said – and you need to know it – but it might be wrong, and it certainly isn’t finished’.

Our understanding of concepts should develop as our experience of the world (including formal education) develops. For this to happen we have to remain open-minded and such open-mindedness can be encouraged by teaching from the outset that there is no authoritative body of knowledge that is fixed for all time but rather a living, growing, changing body of knowledge that is part of a long-term and ongoing cultural dialogue. This dialogic approach encourages young minds to stay in dialogue with the subjects they study and with the wider world long after the original teaching episode has ended. I think it inducts them into Oakeshott’s ‘conversation of mankind’ or the ‘dialogue of humanity‘. I have written more about this in the context of the educational value of P4C here.

So for all these reasons I find the outcomes of the EEF reports unsurprising – teaching through dialogue is a good idea. However, learning how to dialogue is not as easy as we might like to think and a key part of any dialogic education is to teach children how to do it. Our book expands on this and one method is suggested in this blog.

One final thought. The value of dialogue and dialogic thinking goes well beyond attainment at school; it is about the way we engage with ‘the other‘ wherever we encounter it. Laura D’Olimpio of Australia’s University of Notre Dame quoted Jeremy Waldron while discussing the moral purpose of education at a PESGB conference in Birmingham in July 2017:

“…the identity that we should be teaching children to recognise is an identity that involves ‘recognising humanity in the stranger and the other’ and responding humanely to the human in every cultural form.”

If teaching children to dialogue brings this vision a little closer, then it surely has a place in the school curriculum regardless of its impact on attainment.

As always much of what I have written here is drawn from conversation with Rupert Wegerif, now Professor of Education at Cambridge University (I would urge you to read his works). Inspiration is also taken from many conversations with Diane Swift, Director of Keele and North Staffordshire Primary SCITT.

August 6th, 2018 at 19:12

[…] Neil Phillipson thinks the reverse potentially in that we can develop cognitive skills free from subject knowledge, but he does agree with Martin’s post (and references it). […]