Care in the Community (of Enquiry)

“All real living is meeting”

Martin Buber, I and Thou

During the days before Christmas, while shopping in a busy arcade in Chester, I stopped to listen to a male voice choir as they sang carols. It was one of a few occasions this year when I felt infused with the ‘Christmas Spirit’; I was, for a short time, a part of a community of people sharing a difficult-to-define feeling of togetherness and good will. It was one of those occasions when, fleetingly, the boundary that divides ‘me’ from ‘the world’ seems to dissolve. A similar relationship with others can be experienced when a person is drawn into dialogue and I want to argue that one way in which this is made possible is through ‘care’, which I will relate to the notion of ‘caring thinking’ as advocated in philosophical communities of enquiry.

In his 1958 book I and Thou, the Jewish thinker Martin Buber distinguishes between what he calls just experiencing others and entering into relation with them. When we experience others we see them as objects external to ourselves; we seek to learn about them, but always from our own external perspective: “The man who experiences has no part in the world. For it is ‘in him’ and not between him and the world that the experience arises. [The world] does nothing to the experience, and the experience does nothing to it.” Buber referred to this as an ‘I-It’ attitude which, although necessary for day-to-day life, does not allow one to enter into genuine dialogue but rather to engage in instrumental transactions. In the ‘I-Thou’ attitude by contrast, we encounter the other as a whole being; rather than gaining experience of each other in our individual minds, we encounter each other in a space that Buber referred to as the ‘in-between’ – our minds enter into relation with each other. “Relation is mutual. My thou affects me as I affect it.” For Buber, entering into dialogue involves entering into an ‘I-Thou’ relationship with the other.

This kind of immersive experience – this visit to ‘the in-between’ – is indicative of, or perhaps a necessary condition for, dialogue. But how do we create an environment in which such an experience can arise?

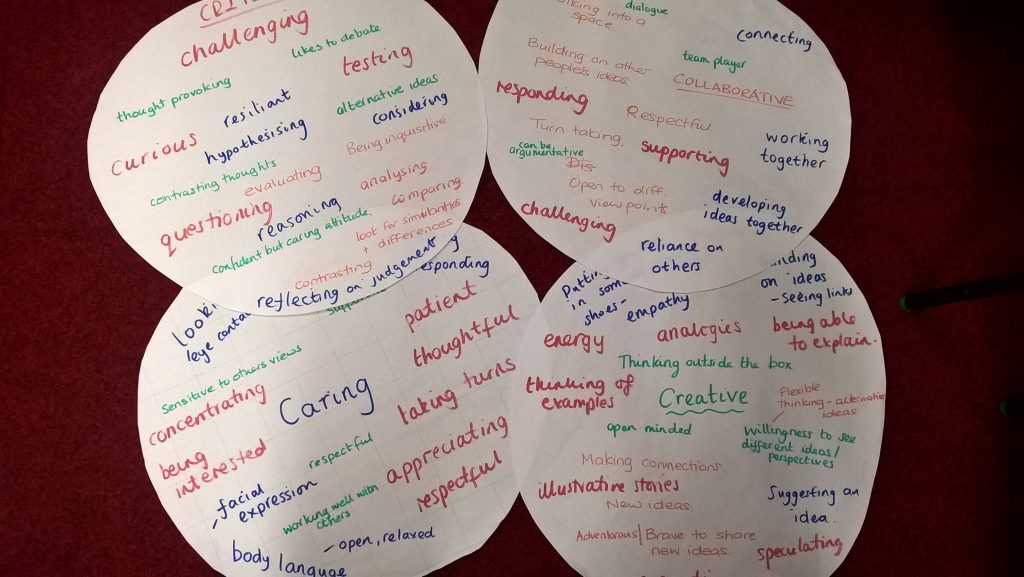

Perhaps one way is to develop a sense of care for others. In Philosophy for Children, caring thinking is encouraged through the development and application of simple ground rules such as ‘We listen attentively to each other’, ‘We imagine how others are feeling’ and ‘We treat all ideas with respect’. These are helpful and important, but perhaps represent only the beginning of an understanding of the significance of care in the community of enquiry.

Following Buber, an I-Thou-type relationship requires us to care not just for the perspective of another on a particular issue, but for why they hold that perspective, for what they care about and for who they are. The English root of the noun ‘care’ is caru meaning ‘sorrow, anxiety, grief’ and also ‘burdens of mind’ and ‘serious mental attention’. Perhaps when we care for another we take on a mental burden which involves the disposition to ‘be interested’, to actively ‘seek to understand’ through an exchange of questions and answers and to ‘suspend judgment’. We enter into a relationship in which we are willing to feel sympathy, sorrow and joy with another.

Just as we hope to come to understand the other, so, in a dialogue, we seek to make ourselves understood; we need the disposition to reveal who we are too. In the process of revealing ourselves in this way, we can come to understand ourselves better – what is it that we care about, and why? In this intimate relationship, participants in a dialogue might also develop or even transform themselves as they encounter new people, new perspectives and new ideas and learn more about what is worth caring about (including dialogue itself).

In her article ‘The Other Dimension of Caring Thinking’, Ann Margaret Sharp argues that

“…the classroom community of enquiry offers children the opportunity to discover values, things, ideas, ideals and people that they can care about“.

And she reminds us, through Heidegger, that “care is the source of all human judgment making, willing and action”. It is only when we genuinely care about something that we find ourselves wanting or willing to act – willing and action are rooted in care.

As we all know, ‘I don’t care!’ is a statement easily made as a defense against showing interest, being thoughtful and taking action. Sharp says that “If I really don’t care about anything outside my own survival, the possibility of a just society is non-existent”. If the community of enquiry is a space in which children learn to care and discover things that are worth caring about – perhaps things like justice, goodness and beauty – and if this capacity to care leads them to take action in relation to such things, then this strikes me as another powerful argument for the presence of Philosophy for Children in the school curriculum.

And once we learn about the value of care – about entering into I-Thou-type relationships with others and allowing them to reveal to us the interest in things – then it will help us in all aspects of our lives. Not least, it will help teachers and children to form meaningful relationships and to discover the interest in things together. Sharp says that “If teachers don’t care about their students, not much educational growth can take place. Rather, a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness on the part of both children and teachers is almost a certainty”. Perhaps the same can be said if students ‘don’t care’ about their lessons, or their teachers. If, on the other hand, a teacher and her students pass through the gateway of care into the relation of dialogue, not only can she draw them into the incredible journey of education, but they can also transform her; as Buber says, in I-Thou relationships, where ‘my thou affects me as I affect it’, “We are moulded by our pupils” and “How we are educated by children!”

There seems to be a synergistic relationship here – care opens the door to dialogue and dialogue helps us to care. But without care and without caring thinking, there is no dialogue. All the algorithmic attempts to follow our ground rules for critical and creative thinking– to give examples and counter examples, to evaluate reasons and arguments and spot faulty logic, to listen and to speak one at a time do not add up to dialogue. If, ultimately, we don’t really care then we will never visit the in-between, never come into relation with our ‘Thou’, and always have a boundary between us, our community and our world.

Dialogue and care are so much needed to improve education and to improve our world. In the absence of the ‘Christmas Spirit’, in the absence of community cohesion in so many ways, the community of enquiry is a place where all of us – young and old – can learn what’s worth caring about together.

You can read Ann Margaret Sharp’s article here.

21st Century Learners offers a range of strategies for the development of dialogue in schools and other settings – please do explore this site and get in touch if you would like to know more.