The (Multiple) Purposes of Science Education

Biesta’s model of the multiple purposes of education (see previous post) provides a framework for exploring big questions about the aims of schooling. But can it usefully be adapted to help the leaders of individual subjects to explore the purposes of their provision, and ultimately to develop a driving vision?

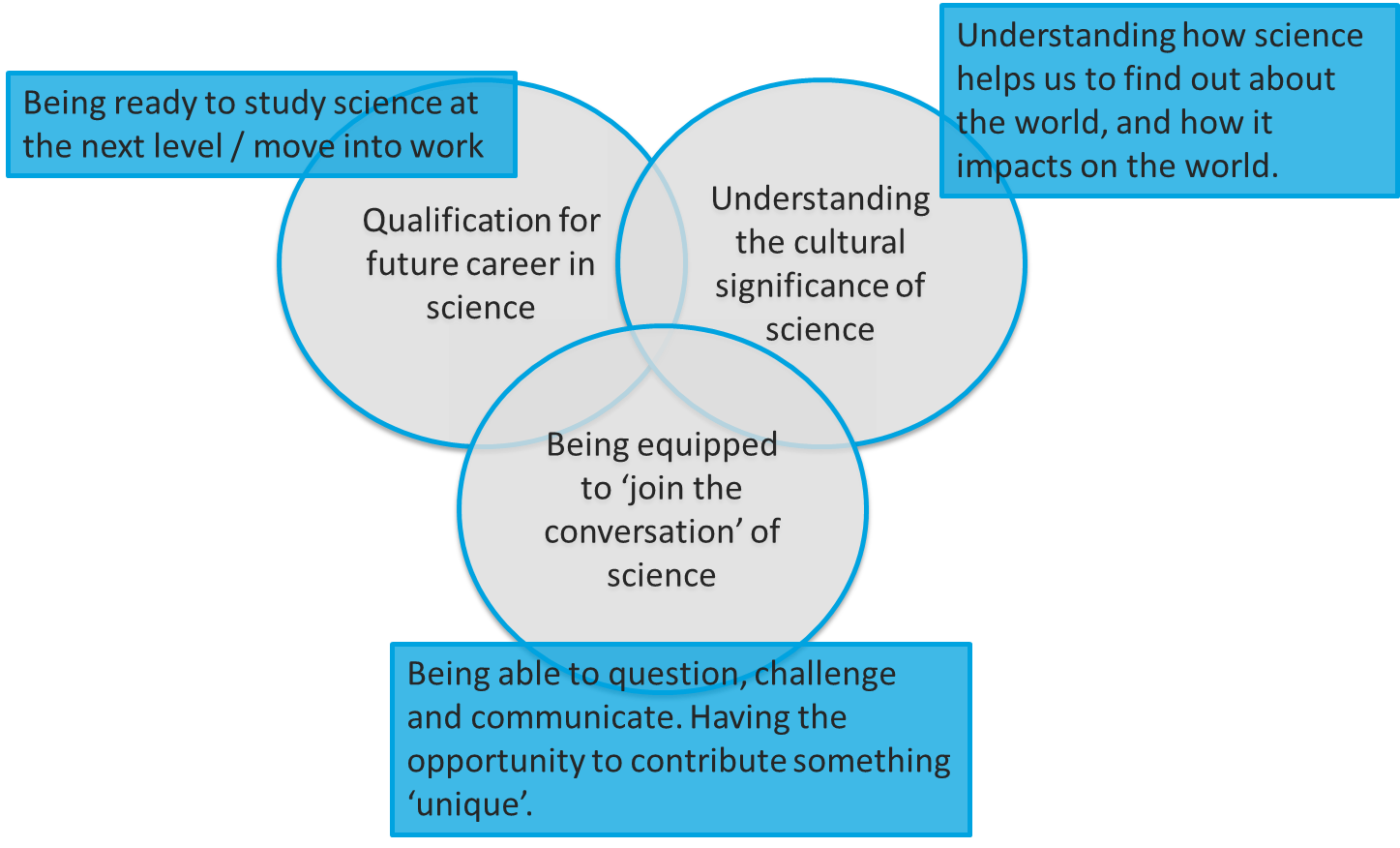

In recent meetings with science subject leaders (at KS2 and KS3) I have suggested the following model as a starting point for discussing the broad purposes of science education and then for developing a set of more specific aims and a vision statement.

Here ‘Qualification‘ refers to the body of knowledge, skills and habits of mind needed to go on to study science at the next level and ultimately to take up a scientific career. This encompasses most of the common aims of science (considering science as both a noun – a body of knowledge – and a verb – a way of generating new knowledge and understanding through enquiry). It encompasses the aims of the 2014 National Curriculum for England. So is there time, and is there a need, for anything else?

‘The Cultural Significance of Science‘ is an interpretation of the purpose of socialisation (see previous post). It invites us to consider the cultural and social impact of science in the past, present and future. It also invites a broader analysis of what science is and how the scientific community works within the context of society. More specific aims that might fall within this sphere of purpose might include:

- exploring the relationships between scientific ‘truth’ and the truths provided by religion and philosophy; exploring the boundaries between these traditions and the limits of science in both historical and contemporary contexts

- investigating the impact of scientific advances on society (past and present), and the limitations placed by society on the work of scientists (the view expressed in the National Curriculum that these things are best studied elsewhere in the curriculum seems to me contestable)

- looking at scientific careers and the economic importance of science

- exploring the process of peer review and publication and its impact on collaboration in the scientific community

This is not intended to be an exhaustive and certainly not a prescriptive list. It’s simply an invitation to science teachers to consider a broad range of aims and to decide which form a part of their vision for a ‘good’ science education. Some may be complementary to ‘Qualification’; others may not, and then we have the responsibility of deciding whether their place in our curriculum can be justified.

The final area of purpose – derived from Biesta’s ‘Subjectification‘ (see previous post) is ‘Being Equipped to join the conversation of science‘. (I suspect that Biesta would regard much of what follows as further socialisation, and comments on what subjectification might look like in science are welcome). Perhaps this is less about curriculum content and more about ways of working that might open up opportunities for children to make unique contributions and to ‘find their voices‘. Teachers might think that valuable aims include:

- giving children experience of ‘authentic’ scientific enquiry (regardless of whether you believe this is the best way of learning subject content)

- creating opportunities for children to communicate their ideas to a variety of audiences and through a variety of media

- developing children’s capacity to engage critically and creatively with science: working critically with evidence, examining ethical questions, making connections to other subject areas etc.

- encouraging children to challenge each other’s ideas: to demand reasoning and evidence – to be open to ‘the other’ and to changing their ideas

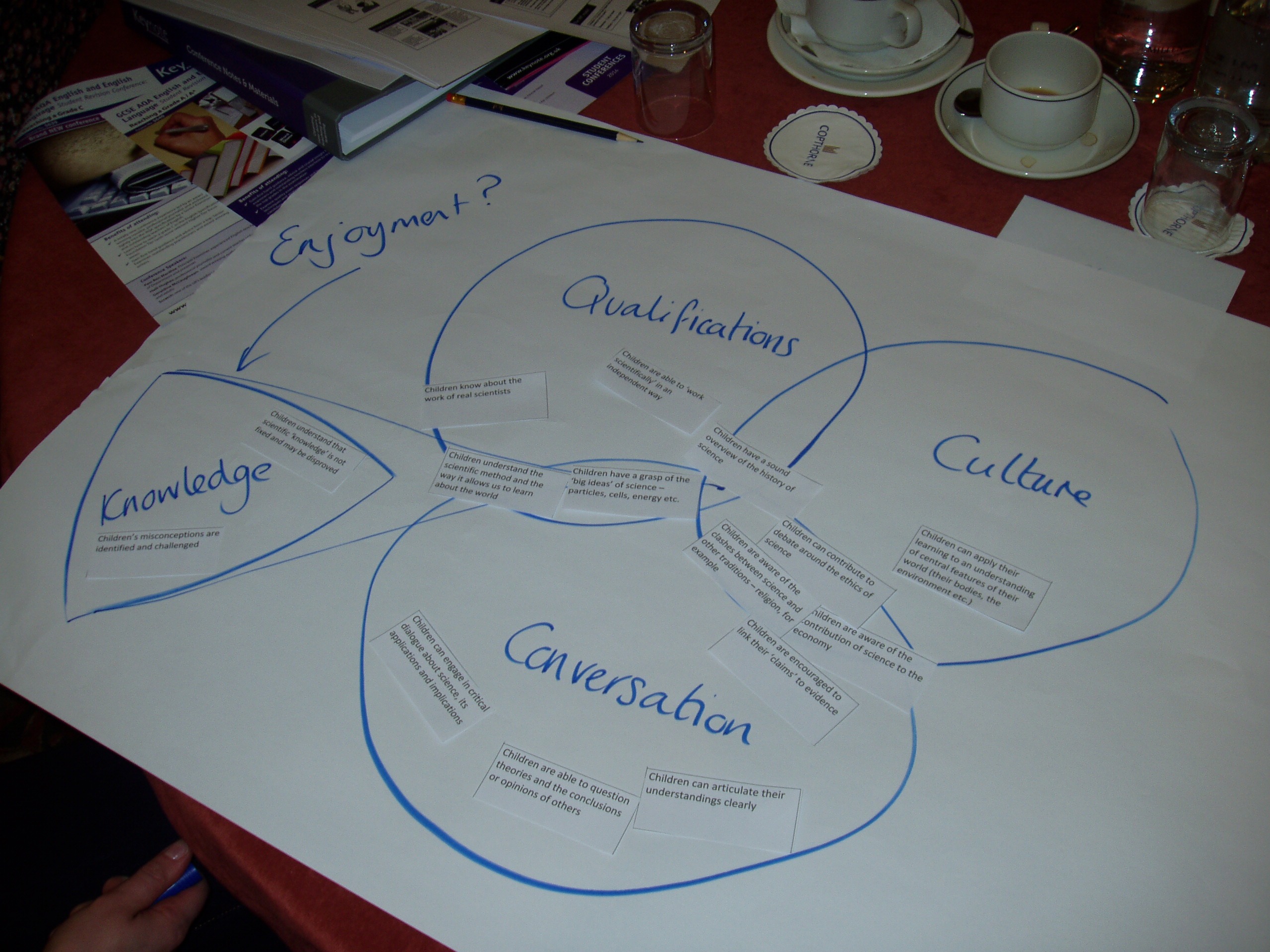

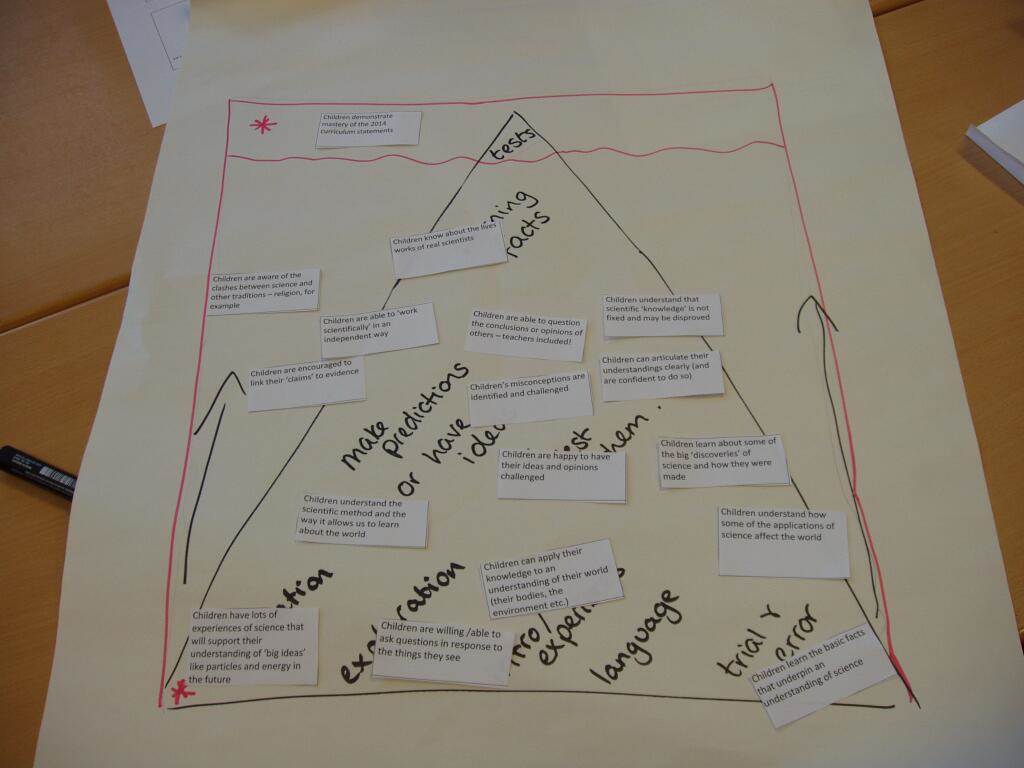

These are just examples intended to begin a conversation. When I have engaged in such a conversation with teachers, I have always been struck by how much they relish the opportunity to ask fundamental questions about the subject they love. Here are some pictures of their emerging ideas:

The process might be a useful one for teams to engage with in school. Working together to establish a clear sense of purpose and a set of aims puts teams in a better position to make decisions about pedagogy; this will be the subject of subsequent posts.

Some teachers have been inspired by these discussions, and have written powerful vision statements to take back to school. Others, however, have been quick to question whether there is time for us to engage with all of this in the face of the pressure of targets and ‘Ofsted style’ lesson observations. Sometimes I am confronted with the assertion that ‘This is not for us to decide – we must do what we are told’. But what are the consequences if we adopt this position? Does this mean that teachers should abandon the right – the responsibility – to engage critically with decisions about what is best for their pupils and what best practice looks like in their subject? If we want our science provision to become ‘outstanding’, is the best we can do to robotically try to conform to our interpretation of ‘what Ofsted want’ (something that even Ofsted seem to be doing their best to prevent)? Or might it be better to develop (and to keep under constant review, always open to new evidence and to the possibility that we are wrong) a well reasoned and passionately held vision of what good (science) education should entail, and to use this vision to drive decisions about pedagogy, being prepared to tell our story, to share our passion with those who might question us, and to share it with the children we teach?

But what of standards – what of attainment? This is, of course, of huge importance. Would accommodating the three broad purposes outlined here mean compromising on attainment in science (as defined by test scores)? Maybe, maybe not. I think it would lead to more children developing a deep understanding of and regard for the subject and to more of them choosing to study it further. I think they would be better equipped to ‘do’ science and to communicate with others. I also think it would provide those who do not go on to study science with a greater sense of what the subject is for, how it works and the impacts it has and has had. They might also be in a better place to engage in public dialogue around science-based issues, many of which are of pressing importance. Do these benefits justify taking time away from the purpose of qualification? That, I believe, is a question for science teachers everywhere.