Dialogue as a Means and as an End

Yin and yang – complementary forces that interact to form a dynamic system in which the whole is greater than the assembled parts. They give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another (Wikipedia)

In this post I make an argument for dialogic education in terms of the possible purposes and aims of education. I also suggest that dialogue is not only a pedagogical tool for achieving these ends but is actually an intrinsic part of the ends themselves.

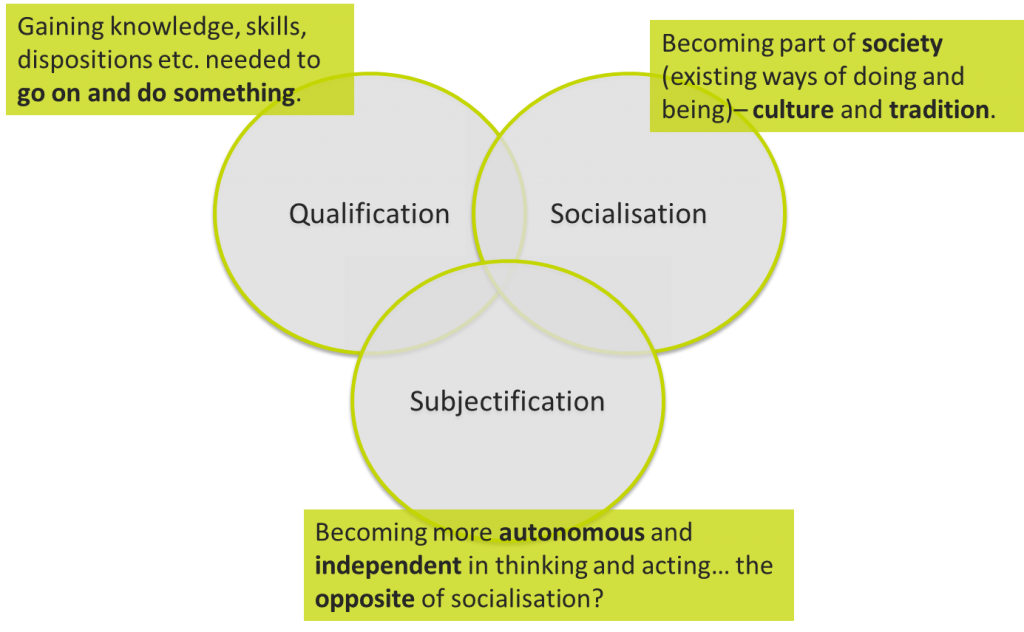

The purposes of education are of course difficult to define. This is because there is no single authoritative view of what education is for, but rather a plurality of different views or different voices in a long-term and on-going conversation. I find Gert Biesta‘s three ‘fields of educational purpose‘ (represented below) to provide a useful framework within which to explore this topic as it admits different perspectives (Biesta, 2010).

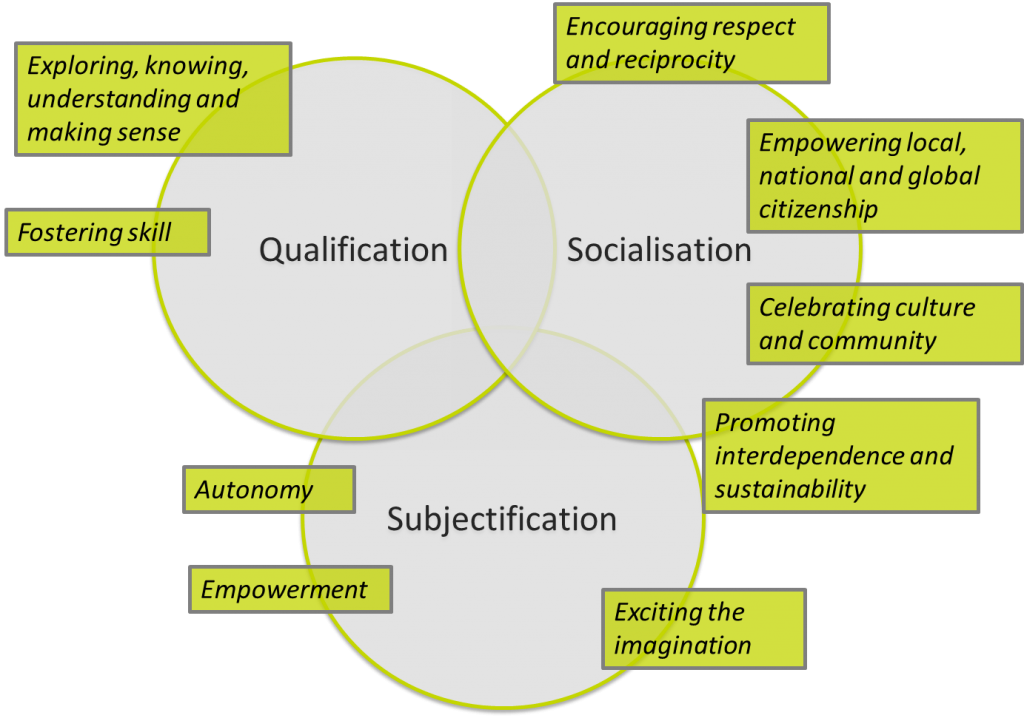

It is possible to make different arguments about the relative importance of these three areas of purpose in the various phases of our school system. These arguments might be had at a national level, or might be left to individual institutions (or even to individual teachers making ‘in the moment’ context-dependent decisions). Having decided where our emphasis lies we can delineate our sense of purpose by developing a set of more specific and perhaps more measurable aims. The Cambridge Primary Review (CPR) has proposed a set of aims for primary education in England (Alexander, 2010). After considering submissions and taking soundings from a wide range of individuals and organisations, the review suggested twelve interdependent aims that constitute ‘a coherent view of what it takes to become an educated person’. I have mapped some of these aims onto Biesta’s diagram:

Where exactly each aim should be placed on the diagram is open to interpretation; the aims and indeed the fields of purpose in which they sit are inter-related (sometimes complementary to each other, sometimes in tension). Empowering children might involve giving them more agency and so might be associated with subjectification, but this might be brought about in part by equipping them with the knowledge they need to make meaningful decisions as agents, which we might associate with qualification. We might argue that empowerment is an inevitable consequence of gaining in knowledge and therefor does not need to be an explicit aim, or we might contend that the disposition to question existing knowledge, to introduce a new perspective (not to speak from a perspective we have been socialised into) and to be subject to the consequential slings and arrows of opposition involves more than having a secure knowledge-base and does need to be addressed explicitly.

CPR suggest three more aims which I have omitted from the diagram as I believe them to belong at its centre. These are Well-being, Engagement and Enacting Dialogue. I would argue that enacting dialogue means embracing a dialogic pedagogy as described by Professor Rupert Wegerif in our forthcoming book ‘Dialogic Education: Mastering core concepts through thinking together‘. The characteristics of this include an acknowledgement that:

- there are always multiple perspectives;

- all conceptual understanding is provisional;

- creative thinking (including the capacity to switch between different perspectives) is essential to learning;

- relationships and making connections between the cultural and academic knowledge that we value and children’s experiences and aspirations for the future are crucial to their engagement in education.

Without such a pedagogy I would argue that:

- we severely limit the possibility of meaningful acquisition of knowledge and skills (see this post and see our book for a more detailed discussion of the link between dialogic education and conceptual understanding);

- we lose the value of any attempt to engage children with their local, national and global communities (see our ‘Inter-generational Dialogue’ project for an example of local engagement and see the Generation Global project for a global example) and to connect them to their culture;

- we deny our children the possibility of finding new perspectives and ultimately adding their voice to the great and on-going dialogue of humanity.

Dialogue and dialogic thinking is the inseparable yin to the yang of our curriculum, not contradictory to our aims as some might claim, but essential to their achievement whichever aspect of educational purpose we choose to emphasise.

In the next post I will respond to suggestions that dialogue is an innate skill and so does not need to be taught explicitly, making the case that as we teach through dialogue, we must also teach for dialogue.

Further Reading

Alexander R. J. (2010). Children, their World, their Education: Final Report and Recommendations of the Cambridge Primary Review. London: Routledge

Biesta, G (2010). Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. New York: Paradigm

Phillipson, N and Wegerif, R (2017). Dialogic Education: Mastering core concepts through thinking together. London, Routledge

July 29th, 2019 at 11:05

[…] N., 2016. Dialogue as a means to an end. 21st Century Learners. Available at http://21stcenturylearners.org.uk/?p=827 Accessed 10 September […]